Recorders came about during the medieval period, though it’s far from the only vertical or end-blown flute ever invented.

Cultures as far back as 35,000 years ago have crafted and used instruments like the recorders. While we now associate this instrument with elementary school music class, the recorder was wildly popular during the Renaissance period.

In this article, we’re going to break down all the parts of a recorder and discuss what they do and how they work. Let’s get started!

Table of Contents

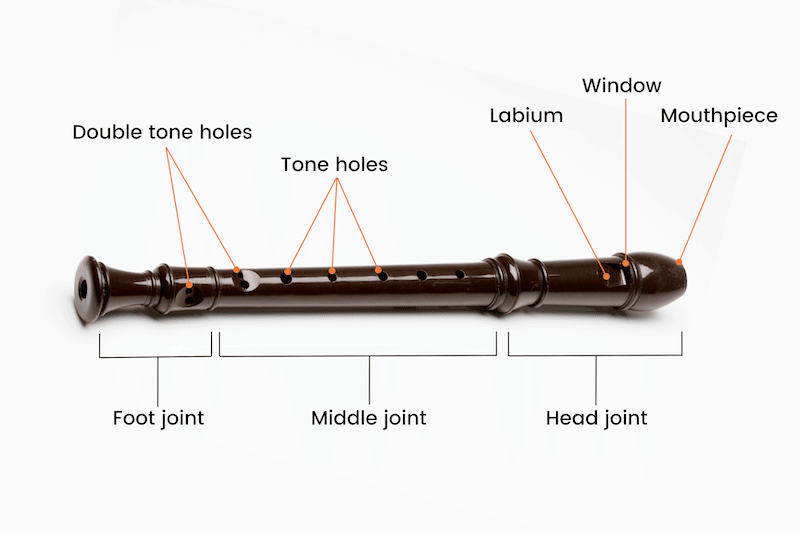

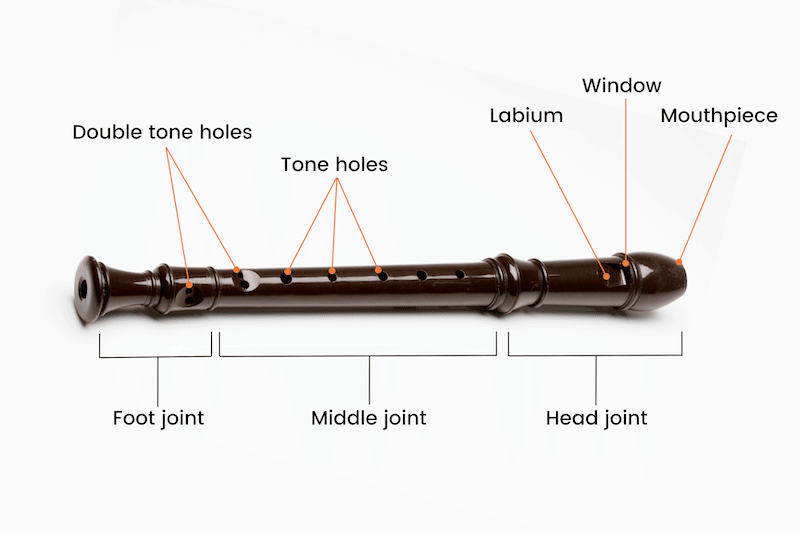

The recorder, much like a flute, is a tubular instrument broken down into three main parts: the head joint, the body joint, and the foot joint.

Recorders come in various sizes depending on the pitch you want—sopranino, descant, treble, tenor, or bass.

Basically, the longer the tube, the deeper the pitch.

People refer to the recorder as an end-blown flute for that reason.

You blow into the head joint and then use your fingers to create the notes by covering the different holes on the body and foot joints.

While recorders are now most often made of resin, wood was their original component.

The descant or soprano recorder, you may know it as the one that we grew up playing in school.

This recorder measures about thirteen inches in length. Resin is the primary material of recorders, and they consist of three joints.

The parts of a recorder start with the head joint, which is the primary part of this instrument.

It contains many intricate sections, and this is where you blow into the recorder to play it.

Each aspect of the head joint is crucial to the recorder’s function, and they all work in tandem with each other to give the recorder its distinct sound.

While sound does come out of the foot joint, it comes out of the head joint as well.

The mouthpiece, sometimes called the beck, is the top part of the head joint that creates the top of the windway.

This is where you wrap your mouth around the instrument to play it.

The mouthpiece is sometimes a monolithic piece of resin, and sometimes there is a second component which is called a block.

The block, sometimes called a fipple, is part of the mouthpiece.

It serves as the bottom of the windway and directs the flow of air into the recorder.

The block’s resin is a differently colored piece, but some recorders don’t even have blocks at all!

As we touched on before, some resin recorder head joints are a single piece.

On wooden recorders, the block has the added feature of absorbing the moisture from your breath.

The windway is the little hole at the tip of the head joint that you blow into, and it comes in two shapes: straight or curved.

Straight windways are great for experienced players.

They allow them for subtle control over the pitch, thus creating a richer sound.

Curved windways offer some air resistance which makes them easier to play for beginners.

While they are easier to play, curved windways lose some of that richness.

Either way, the windway directs the path of your breath to the next component: the window gap.

The window gap is a key component in creating the distinct sound of the recorder.

The window gap is the square hole on the top part of the recorder.

The windway is level with the bottom of the window gap (a part called the labium, which we’ll get to in just a second) that causes vibration when the stream of air moves over it.

The labium, also known as the sound chamber, is the sharp front bottom edge of the window gap.

When air goes through the windway, towards the block, and into the labium, it interacts with the column of air inside the recorder.

This causes the stream of air to split and waver both above and below the labium.

The air that travels below the labium, down the body joint, and out of the foot, a joint creates sound, as does the air that escapes out of the window gap.

To make the sound, the recorder vibrates both externally and internally.

The body joint is the long, tapered middle joint of the instrument, and it’s where all but one of the tone holes are.

When playing the recorder, the column of air inside the body joint interacts with the air being blown into the windway and is then directed by the labium.

The tone holes along the body joint of the recorder are what controls the pitch of the sound as you play.

There are five single-tone holes on the top of the body joint, a thumb hole on the back of the body joint, a double hole at the end of the body joint, and another double-hole in the foot joint.

For the recorder to play properly, the first tone hole needs to line with the window gap.

A curious feature about the tone holes is that they don’t perfectly line up, nor are they evenly spaced—it may look like a mistake, but it isn’t.

This reason is to make it easier to cover all of the holes properly.

Your fingers aren’t all the same length, so it makes sense that each tone hole positions slightly differently along the body to make them easier for you to reach.

This works best when your left hand is up top, and your right hand is at the bottom.

The foot joint, also known as the bell, is the smallest of the three joints of the recorder.

The inside of a recorder does not taper perfectly to the end—the interior of the recorder pinches to a much smaller diameter towards the top of the foot joint and then flares out again at the end of the foot joint, hence why it’s also called a bell.

This bell shape at the end of the foot joint enhances the sound’s resonance as it escapes the end of the recorder.

The foot joint has one double tone hole on it, and you should rotate the foot joint to the right so that its tone hole is slightly out of line with the other tone holes that are on the body joint so that you can more easily reach it with your little finger.

The recorder is perhaps the first instrument we get to know as children, and it’s often considered simple.

Looks can be deceiving, though.

For such a common instrument, it can be rather complicated—but that’s what makes it interesting.

That might also be why it has stuck around so long.

The recorder has gone from feast halls in the middle ages, to performances during the Renaissance, only to fall out of style during the early 1900s.

With its recent surge in popularity, it has become a staple of elementary school music classes.

While we touched upon some of the details, the exact science of how this instrument produces its sound is another far more complicated discussion.

That’s all for our guide to the recorder! We hope that this has helped to demystify this curious little instrument.

Laura has over 12 years experience teaching both classical and jazz saxophone and clarinet. She now resides in California where she works as a session and live performer.

Welcome to Hello Music Theory! I’m Dan and I run this website. Thanks for stopping by and if you have any questions get in touch!